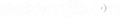

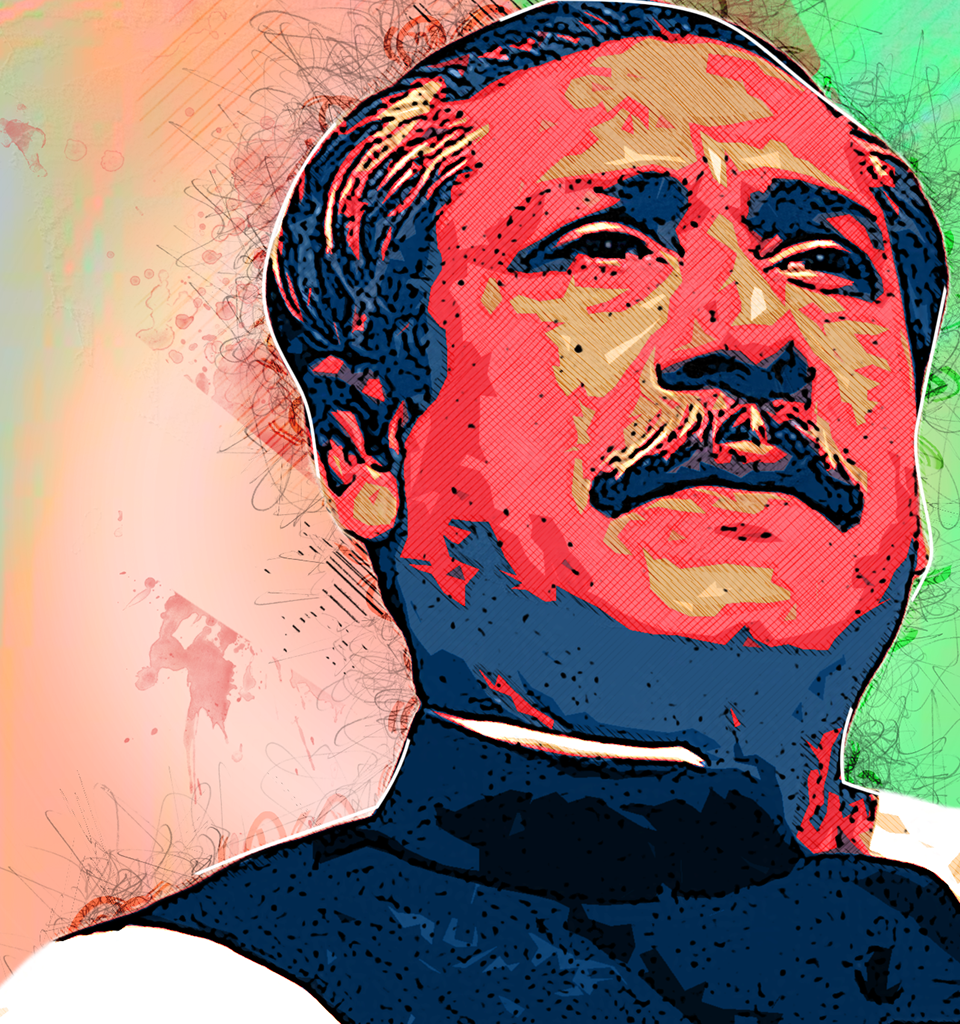

Every classroom, government office, hotel and state building in the fifty-year-old nation of Bangladesh has two portraits hanging front and center. Pictures of father and daughter, Bangladesh Founder Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on the right and the current Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina on the left. Though eerily similar to Mao Zedong’s Communist China or an Arab Gulf monarchy, Bangladesh is completely different both on paper and practice. Bangladesh today is a declared parliamentary democracy, famous for its fertile lands, leading garment industry, overpopulation, and rising economic position within South Asia.

it is no secret that Bangladeshis today have non-stop, unconditional praise for their revolutionary leader and first Prime Minister. When Sheikh Mujibur Rahman first declared independence from Pakistan, the odds were daunting, as the United States-backed Pakistani government met these independence aspirations with a fully-fledged air and land military campaign. Even after Bangladesh triumphed over an exponentially better funded Pakistani military, the U.S. Secretary of State dismissed the newborn nation as a “basketcase.”

Today, the soaring economic hub still faces issues with the world’s largest refugee camp on its Eastern border, overpopulation, internationally prominent corruption, and political hypocrisies exposing Bangladesh as being more of an autocracy than the democracy that it claims to be.

However, credit is earned where credit is due, and the valiant, revolutionary genius, as well as the tragic downfall of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, is a story worth retelling.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, better known as Mujib, was born on March 17, 1920, in Tungipara, a village in the Gopalganj District of modern-day Bangladesh, as the third child in a family of four daughters and two sons. He was born into an upper-middle-class family whose father, Sheikh Lutfur Rahman, was a serestadar (court clerk) in the Gopalganj civil court during the British era. Mujib’s dhak naam was Khoka, which his parents lovingly referred to him as.

At the age of seven he was enrolled in Gimadanga Primary School in 1927 before attending the Gopalganj Public School in class three two years later. In 1931, he enrolled at the Madaripur Islamia High School, where he thrived both as a student and leader, organizing a student protest calling for the removal of an inept school principal.

When Mujib was thirteen years old, family elders fixed a marriage between him and his cousin, Begum Fazilatunnesa. It was Sheikh Abdul Hamid, grandfather to both Mujib and Begum, who initially approached Mujib’s father with the idea, eventually getting the ceremony done in 1938 when Mujib was 18. Mujib and Begum gave birth to three sons (Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal and Sheikh Russel) and two daughters (Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Raihana).

His political calling took off while attending the Gopalganj Missionary School in 1939, when Chief Minister of then-undivided Bengal, A.K. Fazlul Haque and future Prime Minister of Pakistan, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, visited the school campus. Under the leadership of Mujib, a group of students demanded repair of a damaged roof of the school. During this time, young Mujib caught the eye of two leading Bengali Muslim leaders in both British India and later East Pakistan. As a son of a civil servant, Mujib’s integrity and itch for public service were only surpassed by his charismatic leadership and love for his people.

After graduating from Gopalganj Missionary School in 1942, he received both his Intermediate Arts and B.A. in 1944 and 1947 respectively from Islamia College, known as Maulana Azad College today. Upon graduation, Mujib would join Suhrawardy (the Prime Minister of undivided Bengal at the time) and other Muslim politicians in Kolkata to help break up escalating violence before Partition.

Following Partition, Mujib enrolled in the University of Dhaka in newly formed East Pakistan, as a law student. On January 4, 1948, he founded the East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League. His experience on the frontlines during Partition made him an experienced visionary among peers, keeping his eye out for shaping as well as defending the Bengali interests within the newfound Pakistan. Historian M. Bhaskaran Nair describes how Mujib’s role as Suhrawardy’s protege helped him “emerge as the most powerful man in the party.”

Adolescent Mujib witnessed the great famines of 1943 where over five million died and World War II while working alongside leading Bengali leaders such as Suhrawardy and Fazlul Haq during Partition and the early years of East Pakistan. During this time, he witnessed how fellow Bengali revolutionary Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose challenged the British Empire while coming across the works of both Rabindranath Tagore and rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam.

Mujib is remembered for his mediocre academic performance, which was greatly overshadowed by his towering leadership initiatives. Standing at 5’11 with a touch of greying hair, a bushy mustache and dark black eyes, Mujib captivated millions with his thunderous voice and emotional rhetoric, holding his crowds spellbound. A style of speech so poetic and centered on unity before any distinction in class or religion, this larger-than-life persona would only help him grow from local Bengali leader to international personality.

Mujib enters Politics: “The Most Powerful Man in the Party”

Mujib, along with the nearly 42 million Bengalis out of Pakistan’s 75 million population, faced his first real political challenge a year after Partition in 1948. Pakistani Founder and first Prime Minister, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, announced that “Urdu, and only Urdu” would be the state language of Pakistan. Bengalis of East Pakistan immediately rose in outrage in the form of protests launched by Mujib, as leaders communicated their dissent against the removal of Bengali script from government documents and banning of Bengali books. The resulting Bengali Language movement became a cultural revolution that would ultimately pave the road to national independence. Mujib would be arrested twice in 1948; once during the nationwide student strike on March 17, 1948, and again on September 11, 1948, while organizing a movement for the fourth class employees of Dhaka University. His advocacy for the fourth class employees would lead to his expulsion from Dhaka University, thus preventing him from completing his law degree.

Mujib would leave the Muslim League and join the Awami Muslim League (a forerunner to today’s Awami League in Bangladesh) with Suhrawardy in expanding a Bengali and socialist coalition in East Pakistan as an elected joint secretary in 1949.

In 1954, Mujib was elected as a member of the East Pakistan Assembly and joined A.K. Fazlul Haque’s United Front government as its youngest minister. This government would catapult Suhrawardy to become the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan and serve for a year as a Pro-American head of state that split the Awami Muslim League. However, the ruling Muslim League government of Pakistan dissolved this government and again threw Mujib into prison for a third time, setting up a recurring practice that saw Mujib spend most of his youth in prison behind bars. He would be arrested again in 1958, when Pakistani General Ayub Khan staged Pakistan’s first military coup, and for a fifth time in 1962, after 14 months in prison.

Suhrawardy died from a supposed heart attack on December 5, 1962 while in exile in Beirut, which Bengalis to this day are convinced was an assasination ordered by General Ayub for Suhrawardy’s popularity in the upcoming elections. Suhrawardy’s death devastated Mujib as Suhrawardy was his mentor who guided him into politics ever since he was a high school student.

Mujib effectively became the head of the Awami League in 1963, making his first order of business dropping the “Muslim” in the Awami Muslim League to today’s Awami League in an effort for broader appeal to rally non-Muslim communities within Pakistan.

More importantly, economic differences between West and East Pakistan became more clear as nearly twenty years after Partition, Bengalis were poorly represented in Pakistani civil and military services. The only university in East Pakistan was Dhaka University, as the Pakistani central government showed no signs of investing in education or infrastructure in East Pakistan even though it contributed nearly 70% of Pakistan’s overall GDP. This feeling of internal colonization among Bengalis by an alien West Pakistani government was coupled with the routine imposition of martial law and a social atmosphere where Bengali culture was looked down upon and seen as requiring cleansing of Hindu influences.

Mujib came to the fore, once again, in the midst of the recurring injustices and a denial of democracy with his famous Six Point Movement. In 1966, Mujib spoke before a national conference in the Pakistani capital of Lahore where he envisioned a new approach to political life by demanding self-government as well as economic, political and defense autonomy for East Pakistan in response to West Pakistan’s clear display of a weak central government. The Six-Point Movement titled “Our Bangali Charter of Survival” called for:

- A Federal State and introduction of parliamentary form of government based on universal adult franchise

- All departments except defense and foreign affairs will be vested in the hands of the federating units or provincial governments

- Separate currencies for two states or effective measures to stop flight of capital from East Pakistan to West Pakistan

- The transfer of all rights of taxation to the states

- Independence of the states in international trades

- The rights of the states to create’ militia or para-military forces for self-defense.

The Six Point movement was wildly popular all throughout East Pakistan, capturing the support of the Hindu populace as a definitive stance for Bengali autonomy and rights in the future of Pakistan. However, the sentiment in West Pakistan was the exact opposite as Mujib’s plan came across as thinly veiled separatism. Ayub Khan, who was still president of Pakistan after his first coup that sent Mujib to prison, declared in 1966 that those propagating the Six Point program for East Pakistan’s autonomy would be handled through the language of weapons.

“We gave blood in 1952, we won a mandate in 1954. But we were not allowed to take up the reins of this country. In 1958, Ayub Khan clamped Martial Law on our people and enslaved us for the next 10 years. In 1966, our people fought for the Six points but the lives of our our young men and women were stilled by government bullets.” – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

On January 18, 1968, the Pakistan government informed the public that thirty-five individuals had been charged with breaking up Pakistan and turning East Pakistan into an independent state with the covert help of India. The Pakistani Ayub regime’s claim of sedition became known as the Agartala Conspiracy case. Officially named the State vs. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman at the time, the plot was allegedly planned in the city of Agartala located in the Indian state of Tripura. Lieutenant Colonel Shamsul Alam uncovered how Mujib and associates were conspiring to ignite an armed revolution against West Pakistan that would result in secession. Mujib and thirty-four military officers were arrested by the Pakistan Army and jailed for two years before coming before a military court in 1969. In 1967, nearly 1,500 were arrested in connection with the Agartala plot. Strikes and mass civil unrest swept across East Pakistan in response to the state-led actions against Mujib and associates.

The hearings began on June 18, 1968 inside a secured chamber within the Dhaka Cantonment (headquarters for the later Bangladesh army and navy) which served as an opportunity for Mujib to publicize Awami League demands. The tribunal had three judges who witnessed an unsuccessful case against the thirty-five accused of sedition. The final date for the case was February 6, 1969, but a mass upsurge caused the government to defer the date which would only get worse when one of the accused Sergeants, Zahurul Haq, was killed in custody. Mass mobs and arson which burned some of the case’s evidence, led the Pakistani government to drop the Agartala Conspiracy case, releasing the thirty-five accused on February 22, 1969.

The next day, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the other thirty-four accused were greeted with a grand reception at the Race course Maidan, where Mujib was given the Bengali honorific, Bangabondhu or Friend of Bengal. On December 5, 1963, which was the death anniversary of Suhrawardy, Mujib first coined the name “Bangladesh” to replace “East Pakistan” as the name of the land.

Mujib and the Awami League’s political momentum was met with the 1970 Bhola Cyclone, which was the last straw for East Pakistan in their struggle with their Western central government. The cyclone killed over 500,000 and displaced millions, while the Pakistani central government led by then-President Yahya Khan’s Pakistan Peoples Party provided ineffective disaster relief. While East Pakistan blamed the central government for turning a blind eye with an intentionally negligent disaster response, West Pakistan accused East Pakistani leaders for using the crisis for political gain.

The sentiment was clear and present when the 1970 Pakistani general election came along. West Pakistan’s Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) under the leadership of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was completely blown out by Mujib’s Awami League.